Cymraeg / English

|

Back Home |

|

Elan Valley Historic Landscape |

Historic Landscape Characterisation

The Elan Valley

THE ELAN VALLEY RESERVOIR SCHEME

The landscape character of the Elan valley underwent a dramatic change with the construction of the reservoir scheme built between 1893 and 1906 for the corporation of Birmingham, but officially opened amidst much pomp by King Edward VII in 1904. The stunning new landscape that was created during this period, for which this area of western Radnorshire is justly famous, is thus mainly a Victorian to Edwardian in origin, created as a civic project by a distant city, though the valley’s literary and historical associations continue to play an influential role in how the Elan valley is perceived. The qualities that contributed to the allure of the Elan valley’s picturesque landscape — its the gushing streams, steep-sided valleys, and remoteness — were the very same as those which were to make it an ideal site for the Birmingham’s reservoir scheme.

Penygarreg reservoir viewed downstream. Earlier literary associations were well known when work began on Birminghams’s reservoir scheme and are likely to have had a subtle influence on various picturesque aspects of its design. Photo: CPAT 1527.29.

Birmingham, in common with other industrial cities in Britain, came under increasing pressure in the later 19th century to provide adequate water supplies for its rapidly expanding workforce, the population of the city at the time numbering about 650,000. Local water supplies were proving inadequate in terms of volume and had often become polluted, resulting in typhoid and cholera epidemics. As in the case of Liverpool Corporation’s scheme a few years earlier at Lake Vyrnwy, Montgomeryshire, both the quantity and purity of the water were important factors, and Birmingham, like Liverpool, was to seek a solution to these problems in the Welsh hills, some 75 miles from the city.

The Elan valley had been first being examined as a suitable source for Birmingham’s water supply in 1870 by Sir Robert Rawlinson. Nothing further was done for twenty years until 1890 when James Mansergh, the most distinguished water engineer of the day, was appointed as consultant engineer for the project. Mansergh had become familiar with the Elan and Claerwen valleys when working on the Mid-Wales railway in the 1860s. Birmingham Corporation had committed itself to the substantial investment that would be needed to ensure its water supplies to meet both present and future needs and accepted their consultant’s recommendation to acquire the Elan valley watershed which a member of the corporation’s Water Committee described as ‘treasures of untold value’.

The Elan valley scheme, like Liverpool’s early scheme at Lake Vyrnwy, was to be free of the political controversy that was surround the construction of reservoirs to supply English cities in Wales in the second half of the 20th century, as in the case of the Tryweryn reservoir near Bala, built for Liverpool in the early 1960s. Such opposition as there was, was largely concerned with the question of financial compensation and the potential disruption to existing water supplies. Some opposition was to be anticipated from the lord of the manor, Robert Lewis Lloyd of Nantgwilt though the committee in charge of the scheme ‘very prudently therefore came to terms with that gentleman early in the proceedings’. There was no serious opposition to the construction of the 73-mile aqueduct to the Frankley reservoir, near Birmingham, Mansergh noting somewhat sardonically in 1894 that ‘landowners being well enough aware nowadays that they have little chance to stop a great and useful scheme of this character, and that their prudent policy is to acquiesce, with the chance of bleeding the promoters heavily for interfering with their property. Experience showing that in this process they are perhaps more than fairly proficient’. An extensive inquiry was also made into the rights and privileges of the local commoners.

The Garreg-du viaduct, crossing the junction of the Caban-coch and Garreg-du reservoirs, which carries the road up the Claerwen valley. Photo: CPAT 03-c-0602.

The parliamentary bill granting the necessary legal powers to Birmingham Corporation to undertake the scheme became law in 1892. The determination of the area of the watershed to be acquired was in Mansergh’s own words ‘a comparatively easy problem (considered from a water engineer’s point of view), because the contraction of the valley at Caban-coch, and the opening out above of the wide expanse of flat land, fixed at once the position of the dam of the lowest reservoir’. The extent of the watershed was mapped out by accurate survey onto Ordnance Survey plans and a three-dimensional scale model of the area was created, the watershed also being marked on the ground by stone pillars set at intervals. Birmingham was to purchase to entire watershed, an area of about 71 square miles, which Mansergh considered by the standards of 1894 to be ‘an abnormally extensive tract of country to be secured in a mountain district’, representing a large portion of the lands that had been granted by Rhys ap Gruffydd to the newly founded Cistercian monastery at Strata Florida in 1184.

Records of rainfall had been kept by the Lloyds of Nantgwilt since 1870, which indicated an average annual rainfall in the area of the watershed of about 70 inches, which over the area of the watershed would amount to an average of about 100 million gallons a day. Of this figure, the parliamentary bill provided for an average of 27 million gallons ‘compensation water’ to be passed into the Elan every day, although the act allowed for a proportion of this to be reserved to create periodic spates to help the fish to run up the river.

The scheme as originally envisaged, allowing for future expansion, comprised six reservoirs, three on the Elan — Caban-coch (partly on the Claerwen), Penygarreg and Craig Goch, and three on the Claerwen — Dol-y-mynach, Ciloerwynt and Pant-y-beddau. It had always been the intention that the work would be ‘carried out by instalments to meet the growing requirements of the districts to be supplied’. The three Elan reservoirs were sufficient to meet the city’s needs in the first decade of the 20th century and consequently the projected Ciloerwynt and Pant-y-beddau dams were never built. The foundations of Dol-y-mynach dam and the Dolymynach tunnel from the Claerwen to the Elan were built at an early stage, however, since the site of the dam would be flooded once the Caban-coch reservoir had filled up, but the dam was never completed as originally envisaged and only a small reservoir was created. The original proposals in the Claerwen valley were to be superseded by the construction of a single much larger dam, built in the late 1940s and early 1950s, described below. A symmetrical pair of hydroelectric power houses below the Caban-coch dam retaining their original turbines and generators which formed an integral part of the Elan valley reservoir scheme.

The Dol-y-mynach reservoir and its unfinished dam in the right foreground. Photo: CPAT 03-c-0681.

Contemporary technology favoured the construction of relatively high, stone-built dams across steep-sided valleys. A feature of the scheme considered by Mansergh to be ‘novel and unique’ was that in order to maintain a sufficient fall in the aqueduct between Elan and Birmingham it was necessary for the water to be drawn off above the lowest dam at Caban-coch. Water is therefore taken off at the Foel tower, at a point just above a weir below the Garreg-ddu viaduct, normally submerged 40 feet below the surface of the reservoir, the viaduct being necessary to carry the road further up the Claerwen valley, replacing the earlier road in the valley bottom. The water is carried from Foel tower in a tunnel excavated below Foel hill and running to the filter beds opposite Elan Village and from thence in the direction of Rhayader. The average height of the three complete dams, Caban-coch, Penygarreg and Craig Goch and was about 120 feet, the thickness of their bases being designed to be just about equal to their height.

The basic construction of the dams was of large irregular blocks of rubble embedded in concrete with a concrete lining six feet thick, faced upstream and downstream with facings of shaped stones arranged in snecked courses. Stone for the core of the dams at Caban-coch, Penygarreg and Craig Goch was obtained from the two quarries specially opened on the same outcrop of conglomerate on opposite sides of the river Elan near Caban-coch — Cigfran quarry to the north and Craig Cnwch to the south, and the Aberdeuddwr quarry on Cerrig Gwynion, just to the south of Rhayader. Facing and other dressed stone was obtained from the quarries at Llanelwedd near Builth Wells and at Pontypridd. Cement came from works on the river Medway in south-east England, being delivered by sea to Aberystwyth and then by rail to the Elan valley. The cost of the Elan valley scheme ran slightly over budget due to the failure to find suitable building stone near any of the dams apart from Caban-coch, and the necessity of bringing additional stone in from further afield.

Building materials were delivered to the Elan valley by means of the Elan Valley Railway, specially constructed by Birmingham Corporation for the waterworks, the first section of the railway to be built, being the three-mile length from Rhayader Junction on the mid Wales section of the Mid-Wales Railway to the depot below the site of the Caban-coch dam, on the north bank of the Elan, which included a cement cooling shed, general stores, coal depot, workshops for carpenters, smiths, fitters and waggon builders, and sawmills. The various railway tracks leading to each of the dams had a total length of 33 miles and was worked by six locomotives capable of transporting 1,000 tons of materials a day.

In addition to the transport of materials, the railway was also used for transporting workmen from the temporary settlement of wooden huts constructed on the south bank of the river, on the site now occupied by Elan Village, occupied by skilled and unskilled workmen and clerical workers engaged on the scheme. Careful enquiry was made of other large contemporary civil engineering schemes to establish best practice in maintaining discipline and lawfulness, avoid drunkenness and illness in a large, temporary, and predominantly male workforce. Problems of nature had arisen just a few years before when a large influx of workers had arrived in a similarly remote rural setting to build the Liverpool Corporation’s reservoir scheme at Lake Vyrnwy, Montgomeryshire. The village was provided with hospitals, schoolroom, public hall, fire brigade depot and canteen. The canteen was unique for its time in being a municipal public house, all the profits of which were devoted to the social welfare of the community, covering the costs of the mission room, recreation room, gymnasium, free library, recreation grounds and bathhouse. Access to the village was controlled by means of a guarded suspension bridge across the river Elan.

Craig Goch dam, viewed from downstream, looking towards the head of the Elan valley. Photo: CPAT 1528.25.

Like other large engineering works, the workforce was drawn from all over Britain. The resident engineer throughout the works was George Yourdi, ‘an expert in cement work’ of Greek and Irish parentage, who ‘has tramped miles up and down the valley, inspecting, directing, controlling, everywhere, on the coldest of frosty winter days or in the most torrid summer heat’. Other engineers engaged upon the work included Eustace Tickell who supervised the construction of the Penygarreg dam, and who also, as mentioned in an earlier section, produced the book entitled The Vale of Nantgwilt: A Submerged Valley, published in London in 1894. Yourdi occupied the house at Nantgwyllt throughout much of the works, the principal offices occupying a site below the Garreg-ddu weir, near the confluence of the Elan and Claerwen.

Survey work and question of valuation and compensation within the Elan valley undertaken on behalf of Birmingham Corporation by the local surveyor and architect Stephen W. Williams, appointed James Mansergh, who had previously worked with him on the railway schemes in mid Wales. Williams was also made responsible for building the village to house the workmen working. Williams had long been engaged upon his researches on the Cistercian houses of Wales and being familiar with local antiquities was instrumental in effecting a realignment of the Elan Valley Railway to avoid the site of the grange chapel near the Elan Valley Hotel. Williams also designed what became the Birmingham Corporation Water Board’s offices in South Street, Rhayader, built originally for his own use in 1893, and was the architect of Nantgwyllt church near the southern end of the Garreg-ddu viaduct, which replaced one drowned by the rising waters of the reservoir, under construction in 1898 and opened in 1903. Sculptured corbels inside the church are thought to include representations of Stephen Williams and possibly of James Mansergh.

Demolition and flooding of existing houses and buildings within the Elan valley was inevitable. As noted by Mansergh in 1894

‘In the execution of these works (in addition to Nantgwilt already mentioned), there will be submerged the residence of Cwm Elan, the little church at Nantgwilt, the school, the Baptist chapel, and twenty farm and other buildings. With these, practically the whole of the valley lands now worked for agricultural purposes will be covered, leaving the area from which the water will be collected a vast tract of nearly uninhabited moorland, used only as sheepwalk.All the manorial and other rights have been acquired so as to stop mining or quarrying of any description, and ample powers are possessed in the Act to prevent any chance of pollution, and ensure the collection of the water in its pristine purity’.

Careful attention was evidently given in the design and planning of the works to cause as little blemish as possible to the landscape of the Elan valley. Where possible, work yards, processing plants, railway cuttings and other essential works of this kind were sited in places where they would eventually be flooded by the rising waters of the reservoirs. Some elements of the works remain visible, however, including parts of the course of the railway tracks to Penygarreg and Craig Goch dams, the brick railway bridge across the Nant Hesgog stream as well as the course of the link to the former Mid-Wales Railway at Rhayader.

A foundations of number of the former houses are exposed during periods of low water, including those of Cwm Elan and Nantgwyllt, the walled garden and road bridge at Nantgwyllt, and the former farmhouses at Ty Nant below Penygarreg reservoir and Dol-faenog below Garreg-ddu reservoir. Various elements of the construction works are likewise exposed during periods of drought, notably the mason’s yard to the south-west of Caban-coch dam, and the stone and timber foundations of a workmen’s hut just to the west of the Craig Goch reservoir, similar to the complete hut which survives near the Elan Valley Visitor Centre.

In the foreground can be seen field walls the foundations of the former house at Garreg-ddu, below Caban-coch reservoir, which gave its name to the Garreg-ddu viaduct. Photo: CPAT 1526.05.

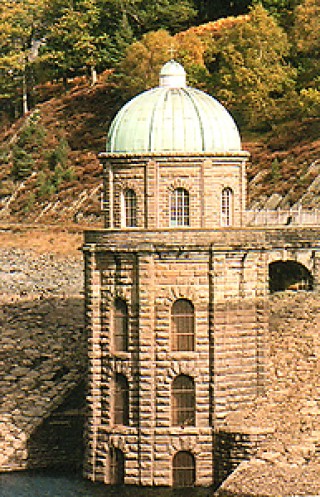

The engineering-architecture of the project lends the area a strong unifying quality, as it is clear that the whole landscape of the reservoirs was carefully designed, not only in the interests of utility, but also consciously as spectacle. The lakeside roads and plantings, the carefully contrived viewpoints, especially that below the Penygarreg dam, and picturesque effects such as the siting and juxtaposition of Nantgwyllt church, Garreg-ddu viaduct and the Foel tower, a visual focal point of the entire scheme, suggest a strong governing aesthetic. The Garreg-ddu viaduct, a is one of the important visual element of the scheme and although well above the submerged weir, in Haslam’s words, ‘gives the illusion on of crossing a shallow lake’. Mansergh’s intentions are quite clear, stating that ‘when more than full water will overflow from all the reservoirs in picturesque cascades down the faces of the dams’, Caban-coch dam being calculated in times of maximum flood to form ‘probably the finest waterfall in this country’.

New roads were built to replace the roads and lanes linking the surviving farms around the Elan and Claerwen valleys, but they are more than this. The railed lakeside carriage rides are part of the original conception, giving access to a landscape designed to be seen, and which like Lake Vyrnwy before it would attract numerous visitors, perhaps especially from Birmingham. Each of the dams was to carry a plaque proudly quantifying its dimensions and the volume of water that it impounded. The Elan Valley Hotel, on the road towards Rhayader, appears to be broadly contemporary, its large function-roomed wing suggesting an early role in the promoting tourism in the area.

In many ways, this was a totally designed landscape: the dams and valve towers are pre-eminent in it, but the engineered roads with their railings, bridges and retaining walls are all part of a scheme whose reach can be mapped in the distribution of even minor architectural features such as culverts and parapets. Not least of these is the series of retaining walls which line the roads: these are variously rock-faced stone, random rubble, and orthostatic blocks infilled with drystone walling, the latter probably derived from a local vernacular tradition of field walling. It was a landscape designed to blend in with the remnant of what had gone before, however. The richer valley-bottom fields and farms, roads and bridges were to disappear below the water. What survived was the remnant broadleaved woodland on the steep, uncultivated valley sides and the more marginal fields and smallholdings on the fringes of the moorland.

Roadside walling in vernacular style on the roadside near Dol-y-mynach reservoir. Photo: CPAT 1539.19.

As in the case of a number of other large late 19th-century and early 20th-century reservoir schemes, Birmingham Corporation’s Elan valley scheme was accompanied by large-scale afforestation, as an alternative to animal grazing and as a means of managing the purity of water runoff, particularly in the immediate vicinity of the reservoirs. William Linnard has stated that ‘over 1,000 acres had been planted before 1918, mainly with Scots pine and European larch, but also with Japanese larch, Douglas fir, Sitka spruce and Corsican pine. One plantation of European larch, with Scots pine for shelter at the higher elevations, planted in 1904–05, was awarded the Silver Medal at the Royal Agricultural Society’s show in 1919’. The plantings were carefully blended in with the existing ancient and replanted broadleaved woodland which formerly existed around the valley sides, of which remnants survive around the fringes of the Caban-coch, Garreg-ddu and Penygarreg reservoirs. Most of the catchment area for the Elan reservoirs was to remain unplanted, however, experience elsewhere having shown that the loss of water by transpiration resulting from afforestation, unlike much of the neighbouring hill land in Ceredigion and north Breconshire which is now cloaked in forestry planted in the early 20th century.

This engineering-architecture has a strong stylistic signature and constructional vocabulary. It is a kind of civic baroque, and is very theatrical, which has become popularly styled ‘Birmingham Baroque’. It relies on exaggeration: the use of over-scaled detailing on the stonework of the dams, for example, is used symbolically to suggest strength; the materials were presumably largely local, and it seems likely that the designers of the scheme were seeking a style that would somehow be apt for the rugged terrain; its context therefore is at least partly in the long-fascination with the picturesque in English architecture and landscape architecture.Penygarreg valve tower, viewed during a period of low water levels. Photo: CPAT 1527.31.

Elan Village, much of which is dated 1909, was built to house maintenance workers, replacing the earlier timber settlement built to house the workforce engaged on the construction of the reservoir scheme. The village represents a perfect arts and crafts ensemble including houses, estate office, and other ancillary structures. It again uses local stone and possibly slate, but employs styles which were common currency in the arts and crafts movement, and whilst seen as a vernacular revival had little to do with specific regional traditions. The village is best seen as another manifestation of the picturesque, very carefully composed and integrating open spaces and planting as part of its overall design. Its gentler architectural language is perfectly adapted to the domesticity of its purpose, contrasting with the robust muscularity of the architecture of the reservoirs themselves, again fitting into notions of fitness for purpose which would have been common currency at the time.

The works in the Elan valley themselves were carried out by direct administration. The aqueduct, by contrast, was carried out largely by contractors and is generally shows less concern at blending in with its surroundings. The 73 miles of aqueduct linking the Elan valley with the service reservoir at Frankley, about 7 miles from the centre of Birmingham, at 600 feet above sea level, a drop of about 170 feet. For about half its length the water flows at atmospheric pressure in a brick-lined conduit laid in a cut-and-cover trench, but where the aqueduct is below the hydraulic gradient, where it crosses valleys for example, it flows in cast iron pipes under pressure and included, when first constructed, about 13 miles of tunnel. The initial scheme used two 42-inch diameter pipes, to which two more 60-inch diameter pipes were added in 1919 and 1961 which increased the capacity of the aqueducts to 75 million gallons a day. The distinctive and somewhat obtrusive brick-built ‘Washout Chamber’ to the north-east of Coed-y-mynach farm is characteristic of the structures that mark the line of the aqueduct that reaches across Radnorshire and the Midland to the Frankley reservoir, skirting Rhayader, Nantmel, Bleddfa and Cleobury Mortimer.

Part of Elan Village built to house maintenance workers in 1909. Photo: CPAT 1525.07.

The romantic associations of the Elan valley were to be renewed in the novel The House Under the Waterby Francis Brett Young, first published in 1932. Young, born and raised in Halesowen, Worcestershire, was nine when construction work began on the Elan valley reservoirs. In the preface which accompanied later editions of the novel he wrote,

‘In every childhood there are, I suppose, certain features in the physical environment which exercise a preponderating effect on the imagination. Such, for me, without doubt, was the building of the Elan Valley reservoirs which impounded the wild waters of the Rhayader Massif in Radnorshire, diverting them from their natural outlet, which was by way of the Wye and the Bristol Channel to the Atlantic, into the sewers of a city which lay on the eastern side of the central watershed, and discharging them finally, by way of the Trent, into the North Sea.’

The House Under the Water was one of a series of Midlands novels by Young set ‘like beads along the string’ that was the Elan valley scheme’s pipeline and in this instance set in the border country popularized by late 19th and early twentieth century authors as A. E. Housman and Mary Webb. Its precursor, Undergrowth, written in collaboration with his brother and published in 1911 when he was in his twenties, also describes the building of a dam in a Welsh valley. His novel, The Black Diamond, takes place along the track of Birmingham’s Elan valley aqueduct. The House Under the Water which charts the romantic entanglements of Griffith Tregaron and his family from their removal from Worcestershire to the ancestral seat at Nant Escob, set in a deep Welsh valley, and the eventual abandonment of the house and valley as it was slowly drowned by the flooding of the river Garon. One of the underlying themes of the novel, by a novelist widely admired during his lifetime but considered by some to be over-sentimental, was the contrast between the harshness of the Welsh valleys and mountains within easy reach of the more hospitable farming landscape of the Midlands. The nature of the place had irrevocably changed, but Phillipa, the heroine of the novel, no doubt expressed a popular opinion about the Elan valley, that the spirit of the place ‘resurgent, inviolable, had perfected out of man’s disfigurement, a new loveliness surpassing any that conscious man could achieve’:

‘a new earth, if not a new heaven. For the earth that she knew and loved had passed away and the waters lay everywhere . . . in two shining lakes whose clear surface, swept by the draughts curling through the valley, danced with crystalline wavelets, which lapped their shores in an innocent gaiety, or, when flaws of wind passed, spread mirrors of indigo in whose depths the reflected mountains appeared to dream, as though lost in the contemplation of their own still beauty’.

Claerwen dam, started in 1946 and officially opened by Queen Elizabeth in 1952 as one of her first official engagements. Photo: CPAT 03-c-0659.

The severe drought of 1937 provided a warning that the city of Birmingham would need to increase capacity, and although plans for the new reservoir, requiring a further parliamentary bill, were at an advanced stage in 1939 construction work was delayed due to the onset of the Second World War. The dams and reservoirs in the Elan valley were seen as obvious targets for sabotage or bombing during the Second World War since this would threaten Birmingham’s principal water supply and were guarded by employees and units of the Home Guard throughout the war, visible remnants of this period being two hexagonal red brick pillbox gun emplacements in Coed y Foel at the junction between the Caban-coch and Garreg-ddu reservoirs. A small, 35-foot high masonry dam which had been built across the Nant-y-gro stream, upstream of the Caban-coch dam, at an early stage in the late 19th century to supply the workmen’s village was to play a notable role in May and July 1942, being used during the early and highly secretive preparations for Barnes Wallis’s ‘Dambusters’ raids on the dams of the Ruhr valley in 1943. The bombed Nant-y-gro dam survives in much the same condition in which it was left during the war.

Work on extending the capacity of the Elan valley reservoirs was taken up again after the end of the war. The advances in engineering and mechanisation that has taken place during the course of the earlier 20th century permitted the construction of a broader and taller dam than had originally been envisaged, about 1.5 kilometres downstream of the dam proposed for the Pant-y-beddau reservoir. The reservoir, started in 1946 and officially opened by Queen Elizabeth in 1952 as one of her first official engagements, almost doubled the supply of water to Birmingham from the Elan valley.

About 470 men worked on the construction of the dam, 56 metres high and 355 metres in breadth, who unlike the workforce employed on the earlier reservoirs were all housed in the local community and transported to the site by road. The workforce included about a hundred Italian stonemasons due to a shortage of skilled workmen because of the repairs due to war damage being undertaken in a number of British cities at the time, including the restoration work being undertaken on London’s Houses of Parliament. Building materials were mostly transported by road from the railway depot at Rhayader.

The reservoir was to be the largest in the Elan valley complex. It is built of concrete but at considerable extra cost in terms of both materials and labour the dam was faced in rock-faced stonework from South Wales and Derbyshire and incorporated other design features in order to harmonize with the aesthetic standards of earlier dams in the Elan valley. Water is released from the reservoir by either of two 1.2 metre diameter pipes, each side of the dam base, which discharge into the river Claerwen.

Further proposals to extend the capacity of the Elan valley reservoirs were under active consideration in the early 1970s, which focused upon a new ‘High Dam’ which would in effect replace the Craig Goch dam. The scheme failed to go ahead, though it is evident from a report presented in 1973 that this new engineering works would have broken with tradition:The Foel valve tower on the Garreg-ddu reservoir, where water is drawn off to begin its journey to the Frankley reservoir south of Birmingham. The lower part of the tower is normally hidden below the surface of the reservoir. Photo: CPAT 1526.14.

‘at the time of their construction these structures were technological achievements of the highest order. A new and higher dam at Craig Goch would, in our view, best be designed in a style appropriate to its size and the times in which we live.’In addition to the original turbine houses below the Caban-coch dam, hydroelectric turbines were added to the Claerwen, Craig Goch, Penygarreg dams and the Foel tower in 1998. The generating sites have been concealed as far as possible and are connected by underground cables.

The Elan Estate has been managed to protect the quality and quantity of the water supplies since 1892 and partly as a consequence its moorlands, bogs, woodlands, rivers and reservoirs are of national importance for plants and wildlife. Today, the estate is divided into 43 holdings covering some 17,402 hectares, five managed directly by the estate and the remainder are tenants of the Elan Valley Trust. The moorland within the watershed of the reservoirs is predominantly used for sheep farming, together with a limited number of cattle and a handful semi-wild Welsh mountain ponies.

Privacy and cookies